Uzbekistan Language Conflict: A Case Study

On a Sunday afternoon, I met a friend at her house for a play date with our kids. We had met recently at our kids’ school so we started talking about our homelands and the journeys which had led us to the Big Apple. We talked about my life in Dominican Republic, and about a decisive moment in her country during the 80s—of civil war and turmoil—when Russia was trying to regain total control over their territory and lives; a moment that led her to leave her home and family and move to the United States. She recounted how It was a time of great scarcity in which Russia intended to dominate their ethnic group by suppressing Islam, neutralizing the power of Uzbeki leadership by killing, incarcerating, or forcing them into exile, and trying to make Russian the official language in educational institutions. At that time, in her 20s, my friend decided to move to the USA with the little English she knew to further her education (B., Yana, March 2016). As opposed to the phenomenon of Americanization I experienced in Dominican Republic in the 80s and 90s—which was mainly a by-product of massive migrations to the USA after Trujillo’s dictatorship ended in 1961, and of a flourished economy due to our tourism hence a broader cultural exposure—the case of the Russification of Uzbekistan in the 80s and 90s was an imposition, a form of oppression and control. After our brief conversation, I decided to deepen my knowledge into Uzbekistan’s history and language conflict.

Through history, Uzbek language has undergone many transformations due to the migrations, oppression, and invasions of Uzbeki tribes. The Uzbek ethnic group comes from the Turkic – Mongol tribe who migrated from Siberia to create what is known today as Uzbekistan. Between 1500 and 1510, the ruling of Muhammad Shaybani who—being a poet—stressed the importance of the arts, helped developed Uzbek literature; Uzbeki language and educational institutions flourished during that period. The Russian invasion in 1868 and the Russian Revolution of 1917—with the institution of the communist party—delineated Uzbekistan’s territory and completely changed the dynamics of Uzbekies when Russian, Polish and Jewish immigrations (during the 1930s) started to dilute Uzbekies’ identity. However, after Stalin’s death in 1953, Uzbekies began to rise to higher positions of power, and declared independence in 1991 (Accredited Language Services, retrieved, June 4, 2016).

As Uzbekistan reclaimed independence, political instability arose, and migration was in flux; other ethnic groups left the country, leaving today’s population fairly homogeneous.

Nevertheless, because of the changes in ruling, the pure Uzbek language of the 1500 had already been transformed in many ways by 1991: from the Arabic-based script, which was used until Soviet domination to the Cyrillic script (similar to written Russian) introduced during the Soviet Union ruling, and Uzbek Latin-Based script which was made official in 1995, replacing Russian in both commerce and government (EURASIANET, June16, 2016; Uzbekistan: Do you Speak Russian? June16, 2016); this ruling tried to open up Uzbekistan to a wider communication with the outside world, in a time of global market expansion. At the time, this law was perceived by Russian-speakers as a “law on emigration” and de-Russification (US English Foundation, August 2007, para 2), and motivated many Russians to flee the country” (US English Foundation, August 2007).

This shift from Cyrillic to Latin script Uzbek also created a generational gap between adults who were used to the Cyrillic language and younger generations who learned the Latin alphabet. In this transition, educational funding to change all school textbooks fell short and major textbooks

were provided in Latin script while other texts were still in Cyrillic; meanwhile, as part of de- Russification measures between 90s and 2000s, the massive burning of Russian-language books was very common. Similarly, signage (in all businesses, governmental communications, street signage, and media) needed to comply with this change by 2010 (US English Foundation, August 2007) although showing a very slow progress by 2007. Moreover, this change of policy has been considered by some as being the cause of a recession in the advancement of science, education, and culture of the country. (US English Foundation, August 2007).

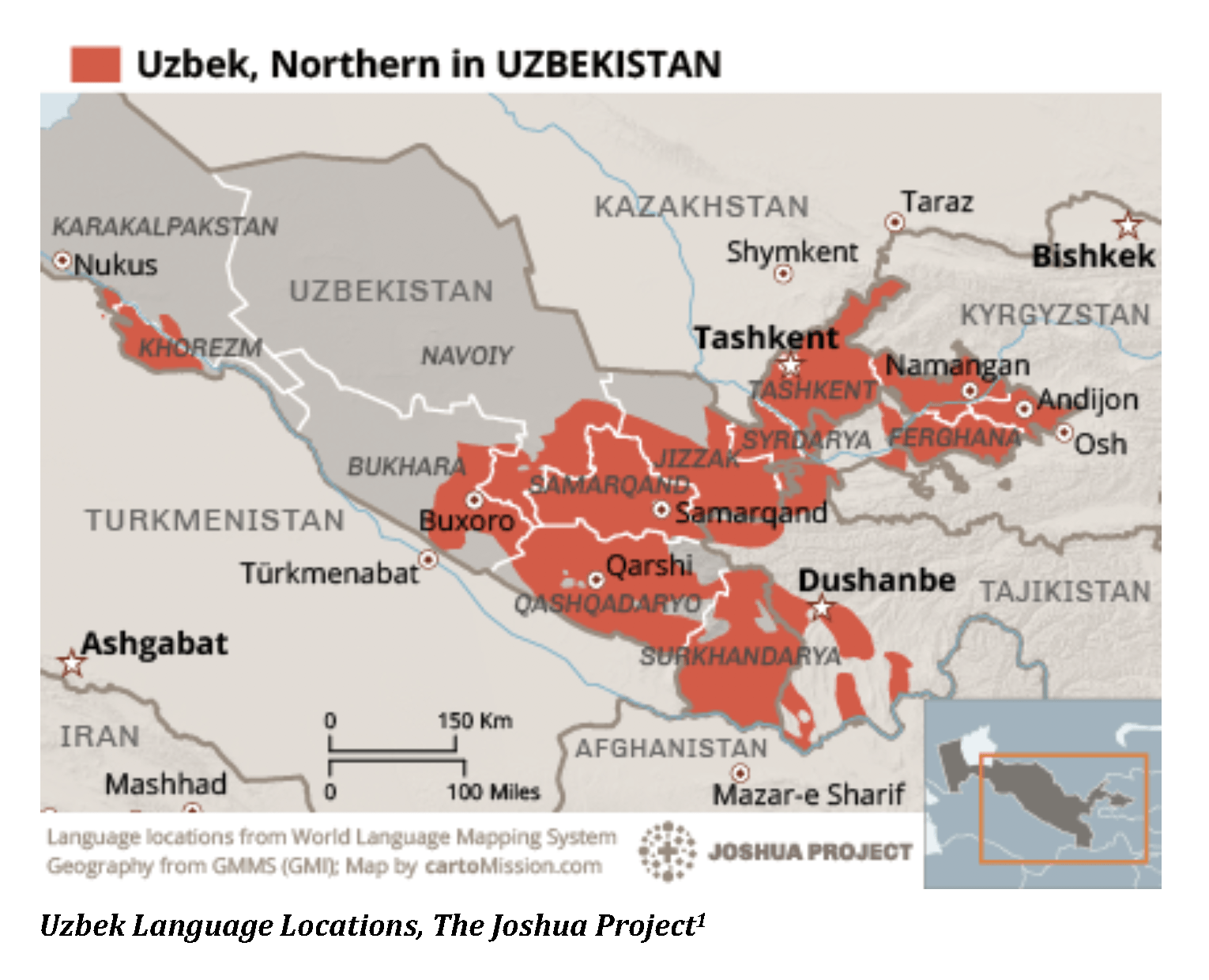

Today, the Republic of Uzbekistan (Northern and Southern Uzbek, Russia) is still in conflict, guarding their borders with Kazakhstan and Kyrzakhstan. Uzbek is the official language— spoken by approximately 23,500,000 people—and it is considered a macrolanguage of distinct variants/dialects. In the territory, there are around 10 spoken languages, and many dialects, although one Uzbek dialect is recognized in educational institutions and mainstream media;1 yet, a group of progressive movements of Uzbek leaders are pushing policy to change the official language to Russian. Although the political atmosphere is tense, nationalism has grown of a history of invasion and conflict, and Uzbeks find in their language an important piece of their identity that could be considerably transformed if Russian were to become the official language (Ethnologue, Languages of The World, retrieved June 4, 2016).

The violent outbreaks and civil wars during the 80s led my friend to leave her homeland and family in search for a better future elsewhere. She married a Russian man here in the USA and has two bilingual English-Russian speaker children who neither speak Uzbek nor have direct connections with that part of their heritage (B., Yana, March 2016). She has been able to preserve Russian as a second language at home because of her own upbringing but in her process of acculturation has lost the roots of her ethnic group.

Her experience exemplifies this current debate, and the future of Uzbekistan is now in the hands of two opposing groups: the remaining Russians and inter-mixed ethnic groups, and the nationalists; the former proposing Russian as new official language and the latter defending Uzbeki, their mother tongue (EURASIANET, June16, 2016). In this debate, highly renown academics have argued that, as any other independent nation, Uzbekistan deserves to have its own language; as stated by Ozod Sharafutdinov, a Tashkent State University professor: “Uzbek became official language in 1989, and that was a right thing to do…Every nation, if it is independent, has the right to give its own language an official status” (EURASIANET, June16, 2016, para. 13). Yuri Podporenko, a Russian-based journalist, on the other hand, argues that it is in “Uzbekistan’s best interests to do more to promote Russian” because seclusion from other cultures is not an option in today’s world and “Russian remains the best channel of information” (EURASIANET, June16, 2016, para. 14). This statement, however, opens up another conversation, of the English language gaining an important space in Uzbekistan’s education—

1 The number of individual languages listed for Uzbekistan is 10. All are living languages. Of these, 5 are indigenous and 5 are non-indigenous. Furthermore, 2 are institutional, 6 are developing, 1 is vigorous, and 1 is dying. Among the most-widespread dialects are the Tashkent dialect, Afghan dialect, the Ferghana dialect, the Khorezm dialect, the Chimkent-Turkestan dialect, and the Surkhandarya dialect.

(Ethnologue, Languages of The World) http://www.ethnologue.com/country/UZ)

Uzbek is considered a macrolanguage (of distinct variants) while Russian is spoken in rural areas. (http://www.ethnologue.com/country/UZ/languages)

as a second language in formal instruction—in order to foster a multilingual society, ready to communicate more effectively in a globalized world.

As Uzbeki tribes have undergone transformations in their culture and language, their roots might get lost in a process of acculturation that already has—and will continue to—damped their identity.

Uzbek Language Locations, The Joshua Project2

Currently, approximately 85% of the Uzbekistan population speak the Uzbek language, 14% use Russian as their primary language while many other people use it as a second language, mainly in business and academia; Russian is considered a lingua franca as it is the preferred language to communicate between different ethnic groups, as per Uzbek Law, 28 Feb. 2005, Sec. 5 (Treatment of Ethnic Russians, 3003-2005 report. June16, 2016). In the web article, Uzbekistan: Do you Speak Russian? author Marina Kozlova (2008) shares a personal story that helps illustrate my point on how these generational language shifts could be the root of the problem and affect, in a larger scale, Uzbekistan’s commerce:

“TASHKENT, Uzbekistan | I had a misunderstanding over an Internet card I was trying to buy from a young merchant in one of Tashkent’s stores not far from the Russian Embassy. He tried to convince me that the card was valid until 2010 while I distinctly saw that it expired in 2009. Suddenly it dawned upon me that we were speaking about the same thing, but the vendor mixed updevyat (nine) and desyat (10) in Russian. When I spoke Uzbek, we were in agreement on the expiration date.”

2 The Joshua Project is an organization seeking to highlight the ethnic groups of the world with the least followers of evangelical Christianity. Wikipedia

https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/14039/UZ

An estimate from the World Factbook (Web, June 12, 2016) shows that Russian is spoken by 14.2% of the population. Table 1.6 below (Aminov, et.al., 2011) shows the high contrast between professional and informal settings where Russian is the language of preference in professional settings (40.2%) while in informal, everyday life, Uzbeki is the most spoken language (44.3%).

This gap could be attributed to the school system since school-age children—who are nearly half of the ethnic Russian population—have limited to zero proficiency in the Russian language because of Uzbeki being institutionalized as the official language while Russian, even though it has no official status, it is a lingua franca of commerce; speakers of both Uzbeki and Russian are 20.7% in informal settings while twice as high (41%) in professional environments.

Conclusion

Language is an expression of culture and, as such, a switch to Russian as official language could leave out a whole population of young adults who don’t know Russian and have already surpassed their formal-education years but who might be bearing children of their own who would then have to speak Russian in order to thrive in a new society and take advantage of opportunities to come. Also, if Russification disseminates to the media, information flows would exclude a large part of the population, becoming accessible to the “recently educated” and alienating the rest, making them “the other;” those who cannot catch up fast enough with the change. The level of education could then become a determinant factor for social separation, stratification, and potential discrimination, as more opportunities are available for those who speak Russian while those who don’t are left behind. In addition, this change could be perceived as a weakness of the Uzbekistan government, and make their territory, yet again, vulnerable to Russian domination.

As of my personal experience, I can say that our identity has suffered enormously in the process of Americanization, even when it has happened in a non-invasive, pacific process. Social classes have been ill-defined by the level of access they have of American culture, the influences a group has adopted, and the ways in which these influences have re-shaped their self and social identities; today, all things American are deemed as “best” and “greater than” while our local product are considered “mediocre” “low-class” and “sub-par.” Though, we have never had language shifts in Dominican Republic, and no pressing language conflicts since Haiti tried to invade us in 1822, we have continuously removed ourselves from our national identity, and give more value to “the other” for the sake of “progress.” Dominican culture is rich in its folk, traditions, and language; we are indeed an amalgamation of cultures, a by-product of colonization, migrations, interventions, and nationalism but we have traded our roots for the illusion of becoming part of the global world; oral narratives, storytelling, poetry, folk songs, perico ripia’o and palo, have slowly disappeared with our elderly (Every Culture, June16, 2016).

This Americanization is also used in my country as a device for division of class and labor, discrimination, and systems of control and oppression that give more to a few and keep leaving behind the majority of the population, who cannot afford—and has no access—to the commodities of a globalized economy, of imported good, international media outlets hence global information flows; all which have come from a process that has overvalued external products and a “cosmopolitan” lifestyle while undervaluing our own resources, human capital, and culture. In the case of Uzbekistan, is it the Uzbek language the major problem in gaining opportunities for its citizens? Is it the lack of a robust Russian language? or would it be the many language shifts—concomitantly with socio-political conflicts—that have created so much confusion and instability in a territory of commerce?

If Russian becomes the official language, would older generations of Uzbekies be left out of any benefits of a raising economy in a globalized world? Would opportunities be available only for those opened to embark in formal education? Would traditions, religious rituals, and oral narratives get lost in time and die with those who could not catch up with the transition, and got caught up in a gap of bearing children in a world with a language foreign to them, and moreover, which carries a long history of pain and oppression? I believe that for a society positioned in a strategic area for commerce in Central Asia, fostering a multilingual society deems more beneficial in the long-term future; however, nationalism, social and self-identity build a strong society, and language is culture, language is society, so Uzbekistan deserves its own identity as a free, independent, country.

References:

- Aminov, K. et.al., Language Use and Language Policy in Central Asia, 2011 Web, June 22, 2016 http://osce- academy.net/upload/file/language_use_and_language_policy_in_central_asia.pdf

- B., Yana. Personal Conversation. March 2016

- Central Intelligence Agency, The World Fact Book,

- Web, June 12, 2016 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/uz.html

- EURASIANET

- Web, June16, 2016 http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/insight/articles/eav091906.shtml

- Every Culture, Countries and their Cultures,

- Web, June16, 2016 https://www.everyculture.com/multi/Bu-Dr/Dominican-Americans.html

- Marina Kozlova. Uzbekistan: Do you Speak Russian? May 21, 2008. Web, June 16, 2016 http://chalkboard.tol.org/uzbekistan-do-you-speak-russian/

- The Joshua ProjectWeb,

- Web, June 16, 2016 https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/14039/UZ

- “Uzbek.” Accredited Language Services,

- Web, June 4, 2016 https://www.alsintl.com/resources/languages/Uzbek

- “Uzbekistan.” Ethnologue, Languages of The World

- Web, June 16, 2016 http://www.ethnologue.com/country/UZ

- “Uzbekistan, Language Research.” US English Foundation, August 2007 Web, June 4, 2016 http://www.usefoundation.org/view/886

- Uzbekistan: Treatment of Ethnic Russians (2003 – 2005). February 6, 2006

- Web, June 8, 2016 https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/eoir/legacy/2013/11/07/UZB100740.E.pdf

- “Uzbekistan: Secondary Education.” State University

- Web, June 22, 2016 http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1652/Uzbekistan- SECONDARY-EDUCATION.html

- World Atlas, “What Languages Are Spoken in Uzbekistan?” Web, June 4, 2016 https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-languages-are-spoken-in-uzbekistan.html